Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine ›› 2025, Vol. 45 ›› Issue (3): 518-527.DOI: 10.19852/j.cnki.jtcm.2025.03.001

Previous Articles Next Articles

Pharmacological effect and possible mechanism of Mudan Huaban recipe (牡丹化斑方) on melasma in mice induced by ultraviolet B and progesterone

LIU Xiaoyao1,2( ), LI Jialin3(

), LI Jialin3( ), WANG Weiling4, FAN Qiongyin5, SU Zeqi6,7, HE Cheng5, WANG Chunguo6, GAO Jian7(

), WANG Weiling4, FAN Qiongyin5, SU Zeqi6,7, HE Cheng5, WANG Chunguo6, GAO Jian7( ), WANG Ting6,7(

), WANG Ting6,7( )

)

- 1 School of Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China

2 School of Chinese Material Medica, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China

3 School of Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China

4 Beijing Research Institute of Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China

5 Beijing Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Beijing Key Laboratory of Neuropsychopharmacology, State Key Laboratory of Toxicology and Medical Countermeasures, Beijing 100850, China

6 Beijing Research Institute of Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China

7 Key Laboratory of Famous Doctors and Famous Prescriptions Under State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China

-

Received:2024-03-23Accepted:2024-07-12Online:2025-06-15Published:2025-05-21 -

Contact:GAO Jian, Beijing Research Institute of Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China. gaojian_5643@163.com;Prof. WANG Ting, Beijing Research Institute of Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine, Beijing 102488, China. wangting1973@sina.com,Telephone: + 86-17812008206; + 86-18435165526 -

Supported by:Beijing University of Chinese Medicine Transversal Project: "Internal and External" Product and Technology Development for Herbal Acne and Blemish Removal(2019110031001241);Youth Project Under the National Natural Science Foundation of China: Revealing the Scientific Connotation of Tongfu Chinese Herb Rhubarb in Treating Ischemic Stroke from the Perspective of "Intestinal Tryptophan Metabolism and Central Microglia Polarisation"(82104440)

Cite this article

LIU Xiaoyao, LI Jialin, WANG Weiling, FAN Qiongyin, SU Zeqi, HE Cheng, WANG Chunguo, GAO Jian, WANG Ting. Pharmacological effect and possible mechanism of Mudan Huaban recipe (牡丹化斑方) on melasma in mice induced by ultraviolet B and progesterone[J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2025, 45(3): 518-527.

share this article

Figure 1 Pharmacodynamic results of MHR on the melasma model mice induced by UVB and progesterone A: observation of skin surface of mice ear; A1: Control; A2: Model; A3: L-MHR; A4: M-MHR; A5: H-MHR; A6: VE + VC; A7: TA. B: typical Fontana-Masson staining images of the epidermal basal layer of ear skin with 40× magnification, scale bar = 50 μm (melanin granules are indicated by blue arrows); B1: Control; B2: Model; B3: L-MHR; B4: M-MHR; B5: H-MHR; B6: VE + VC; B7: TA. C: Statistical results of the mean optical density values of the melanin-positive target area in the ear skin tissue. Control: the mice were injected with saline and treated with animal drinking water; Model: the mice were subjected to progesterone (20 mg/kg) intramuscularly daily and subjected to UV irradiation on alternate days for 21 d to induce a melasma model, and treated with animal drinking water for 30 d; L-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with low dose (2 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; M-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with medium dose (4 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; H-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with high dose (8 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; VE + VC: melasma model mice were treated with vitamin E and C granules solution (0.12 g/kg) for 30 d; TA: melasma model mice were treated with tranexamic acid tablet solution (0.1 g/kg) for 30 d. MHR: Mudan Huaban recipe; VE + VC: vitamin E and C; TA: tranexamic acid; IOD: integrated option density. UVB: ultraviolet B. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance for multimal comparisons. Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 8. Significant difference versus control: aP < 0.01; significant difference versus model: bP < 0.05, cP < 0.01.

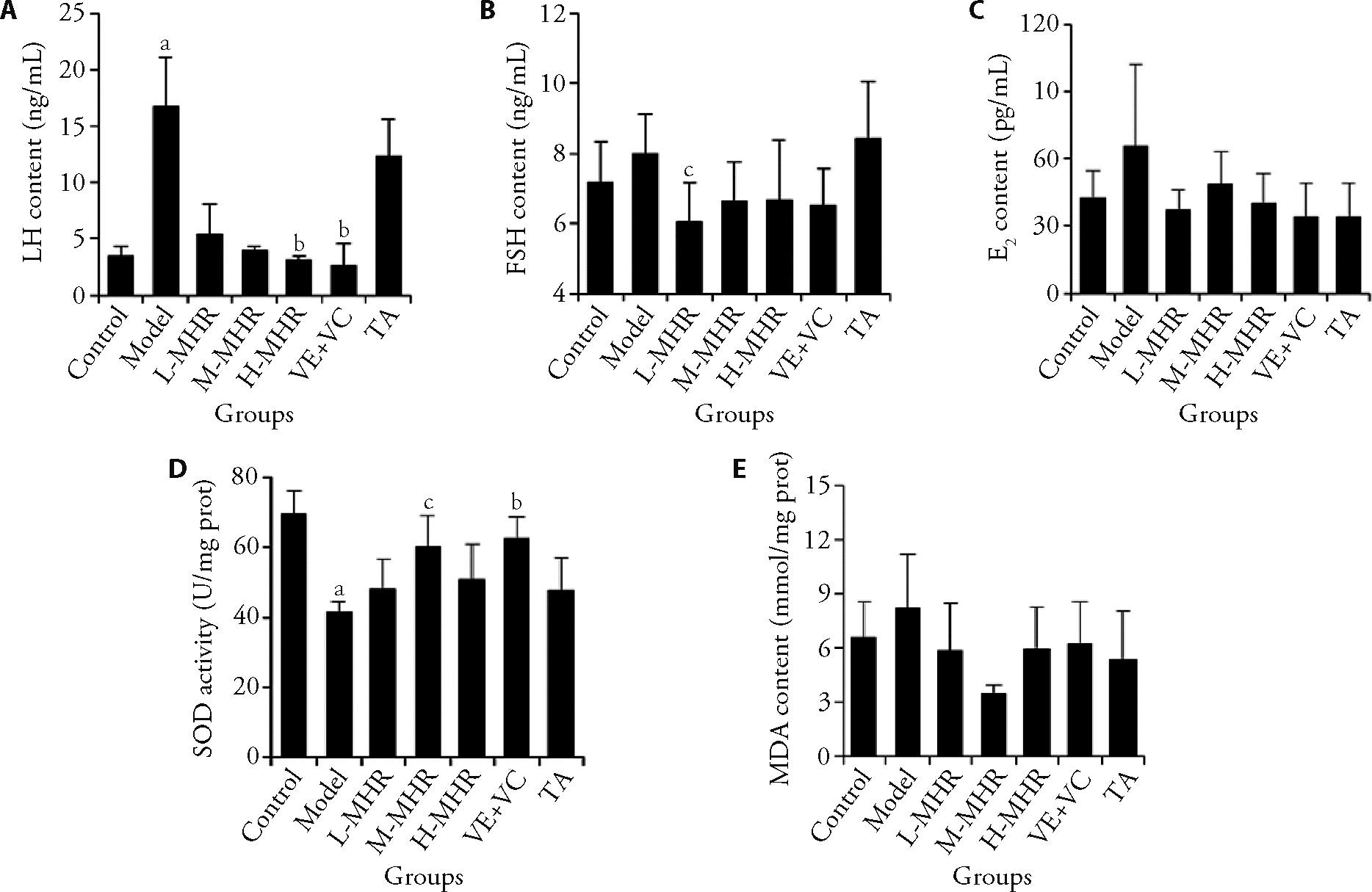

Figure 2 MHR administration improved the sex hormone levels and oxidative stress in melasma model mice A: LH content of mice serum; B: FSH content of mice serum; C: E2 content of mice serum; D: SOD activity of dorsal skin tissues in mice; E: MDA content of dorsal skin tissues in mice. Control: the mice were injected with saline and treated with animal drinking water; Model: the mice were subjected to progesterone (20 mg/kg) intramuscularly daily and subjected to UV irradiation on alternate days for 21 d to induce a melasma model, and treated with animal drinking water for 30 d; L-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with low dose (2 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; M-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with medium dose (4 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; H-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with high dose (8 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; VE + VC: melasma model mice were treated with vitamin E and C granules solution (0.12 g/kg) for 30 d; TA: melasma model mice were treated with tranexamic acid tablet solution (0.1 g/kg) for 30 d. MHR: Mudan Huaban recipe; VE + VC: vitamin E and C; TA: tranexamic acid; UV: ultraviolet; LH: luteinizing hormone; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; E2: estradiol; SOD: superoxide dismutase; MDA: malonic dialdehyde. Statistical analysis was conducted using a one-way analysis of variance when the data were normally distributed and a non-parametric test when the data were not normally distributed. Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 5-10. Significant difference versus control: aP < 0.01. Significant difference versus model: bP < 0.01, cP < 0.05.

Figure 3 MHR regulated the expressions of melanogenesis-related enzyme and proteins in melasma mice A: immunohistochemistry staining of the ear skin tissues with 40 × magnification, scale bar = 50 μm; A1-A5: control group of tyrosinase (A1), TRP-1 (A2), TRP-2 (A3), MITF (A4) and CREB (A5); A6-A10: Model group of tyrosinase (A6), TRP-1 (A7), TRP-2 (A8), MITF (A9) and CREB (A10); A11-A15: L-MHR group of tyrosinase (A11), TRP-1 (A12), TRP-2 (A13), MITF (A14) and CREB (A15); A16-A20: M-MHR group of tyrosinase (A16), TRP-1 (A17), TRP-2 (A18), MITF (A19) and CREB (A20); A21-A25: H-MHR group of tyrosinase (A21), TRP-1 (A22), TRP-2 (A23), MITF (A24) and CREB (A25); A26-A30: VE + VC group of tyrosinase (A26), TRP-1 (A27), TRP-2 (A28), MITF (A29) and CREB (A30); A31-A35: TA group of tyrosinase (A31), TRP-1 (A32), TRP-2 (A33), MITF (A34) and CREB (A35). B-F: Statistical results of the mean optical density values of the positive areas for tyrosinase (B), TRP-1 (C), TRP-2 (D), MITF (E) and CREB (F) in the ear skin tissue. Control: the mice were injected with saline and treated with animal drinking water; Model: the mice were subjected to progesterone (20 mg/kg) intramuscularly daily and subjected to UV irradiation on alternate days for 21 d to induce a melasma model, and treated with animal drinking water for 30 d; L-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with low dose (2 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; M-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with medium dose (4 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; H-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with high dose (8 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; VE + VC: melasma model mice were treated with vitamin E and C granules solution (0.12 g/kg) for 30 d; TA: melasma model mice were treated with tranexamic acid tablet solution (0.1 g/kg) for 30 d. MHR: Mudan Huaban recipe; VE + VC: vitamin E and C; TA: tranexamic acid; IOD: integrated option density; UV: ultraviolet; TRP-1: tyrosinase-related proteins-1; TRP-2: tyrosinase-related proteins-2; MITF: microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; CREB: cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein; Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance for multimal comparisons. Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 5. Significant difference versus control: aP < 0.01, dP < 0.05. Significant difference versus model: bP < 0.05, cP < 0.01.

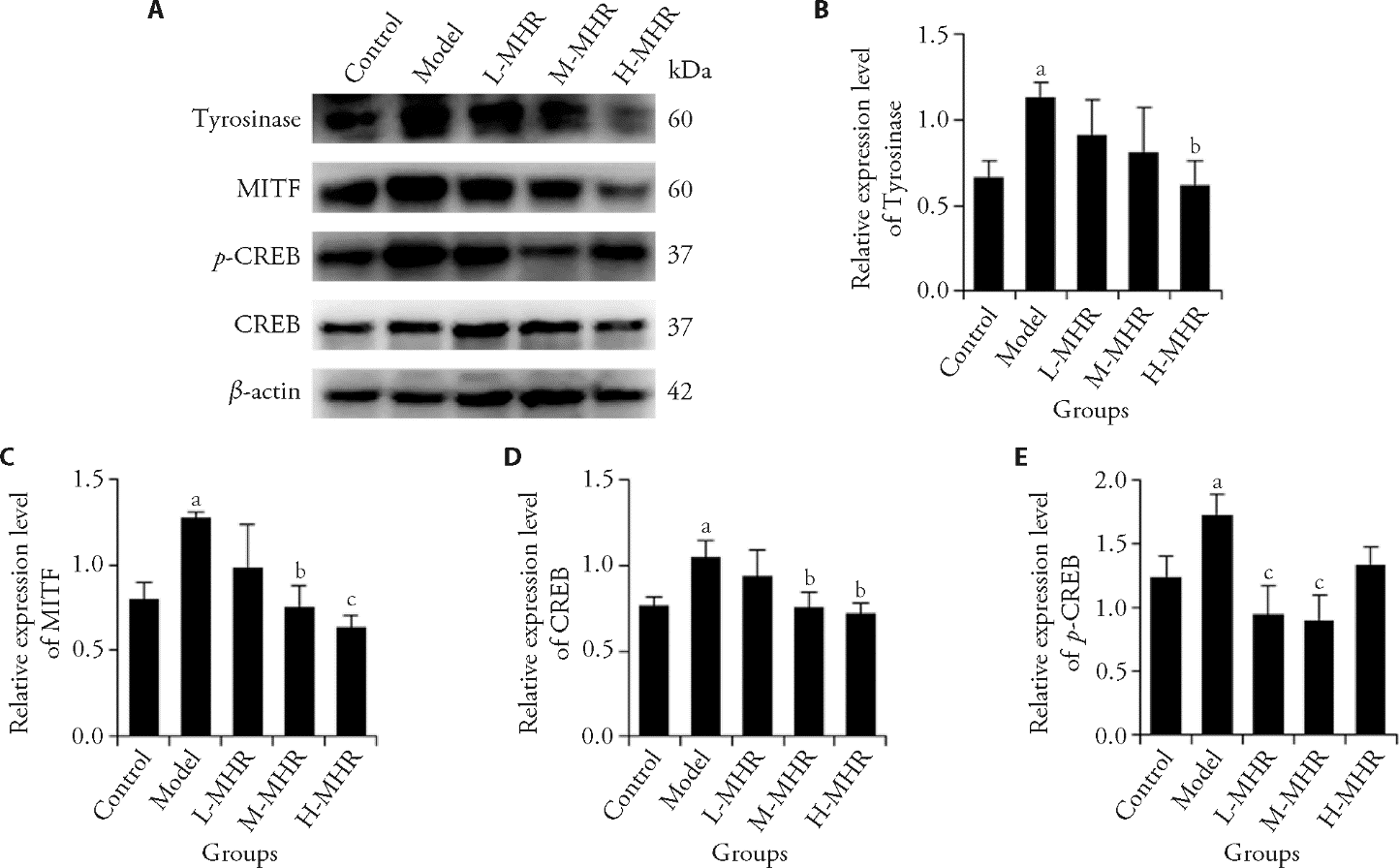

Figure 4 Effect of MHR on the protein expression of tyrosinase, MITF, CREB, and p-CREB in ear skin tissues by Western blot A: representative Western blot image of tyrosinase, MITF, CREB, and p-CREB; B: relative expression level of tyrosinase; C: relative expression level of MITF; D: relative expression level of CREB; E: Relative expression level of p-CREB. Control: the mice were injected with saline and treated with animal drinking water; Model: the mice were subjected to progesterone (20 mg/kg) intramuscularly daily and subjected to UV irradiation on alternate days for 21 d to induce a melasma model, and treated with animal drinking water for 30 d; L-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with low dose (2 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; M-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with medium dose (4 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; H-MHR: melasma model mice were treated with high dose (8 g/kg) of MHR for 30 d; VE + VC: melasma model mice were treated with vitamin E and C granules solution (0.12 g/kg) for 30 d; TA: melasma model mice were treated with tranexamic acid tablet solution (0.1 g/kg) for 30 d. MHR: Mudan Huaban recipe; VE + VC: vitamin E and C; TA: tranexamic acid; UV: ultraviolet; MITF: microphthalmia-associated transcription factor; CREB: cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) response element-binding protein; p-CREB: phosphorylation of CREB. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance for multimal comparisons. Values are represented as mean ± standard deviation, n = 3. Significant difference versus control: aP < 0.05. Significant difference versus model: bP < 0.05, cP < 0.01.

| 1. |

Passeron T, Picardo M. Melasma, a photoaging disorder. Pigm Cell Melanoma R 2018; 31: 461-5.

DOI PMID |

| 2. | Rajanala S, Maymone MBC, Vashi NA. Melasma pathogenesis: a review of the latest research, pathological findings, and investigational therapies. Dermatol Online J 2019; 25: 13030/qt47b7r28c. |

| 3. | Ogbechie-Godec OA, Elbuluk N. Melasma: an up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2017; 7: 305-18. |

| 4. |

Handel AC, Miot LD, Miot HA. Melasma: a clinical and epidemiological review. An Bras Dermatol 2014; 89: 771-82.

DOI PMID |

| 5. |

Babbush KM, Babbush RA, Khachemoune A. The therapeutic use of antioxidants for melasma. J Drugs Dermatol 2020; 19: 788-92.

DOI PMID |

| 6. | Lee AY. Recent progress in melasma pathogenesis. Pigm Cell Melanoma R 2015; 28: 648-60. |

| 7. |

Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: How hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol-US 2019; 18: 458-63.

DOI PMID |

| 8. |

Choubey V, Sarkar R, Garg V, Kaushik S, Ghunawat S, Sonthalia S. Role of oxidative stress in melasma: a prospective study on serum and blood markers of oxidative stress in melasma patients. Int J Dermatol 2017; 56: 939-43.

DOI PMID |

| 9. |

Komirishetty P, Areti A, Yerra VG, et al. PARP inhibition attenuates neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in chronic constriction injury induced peripheral neuropathy. Life Sci 2016; 150: 50-60.

DOI PMID |

| 10. | Kim HJ, Moon SH, Cho SH, Lee JD, Kim HS. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in melasma: a Meta-analysis and systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol 2017; 97: 776-81. |

| 11. |

Lee HC, Thng TGS, Goh CL. Oral tranexamic acid (TA) in the treatment of melasma: a retrospective analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 385-92.

DOI PMID |

| 12. |

Mishra SN, Dhurat RS, Deshpande DJ, Nayak CS. Diagnostic utility of dermatoscopy in hydroquinone-induced exogenous ochronosis. Int J Dermatol 2013; 52: 413-7.

DOI PMID |

| 13. |

Nomakhosi M, Heidi A. Natural options for management of melasma, a review. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2018; 20: 470-81.

DOI PMID |

| 14. |

Zhang Y, Zheng X, Chen Z, Lu L. Laser and laser compound therapy for melasma: a Meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 31: 77-83.

DOI PMID |

| 15. | Manuskiatti W, Yan C, Tantrapornpong P, Cembrano KAG, Techapichetvanich T, Wanitphakdeedecha R. A prospective, split-face, randomized study comparing a 755-nm picosecond laser with and without diffractive lens array in the treatment of melasma in Asians. Laser Surg Med 2021; 53: 95-103. |

| 16. | Nair AB, Jacob S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm 2016; 7: 27-31. |

| 17. |

Deshpande SS, Khatu SS, Pardeshi GS, Gokhale NR. Cross-sectional study of psychiatric morbidity in patients with melasma. Indian J Psychiat 2018; 60: 324-8.

DOI PMID |

| 18. |

Feng L, Shi N, Cai S, et al. De novo molecular design of a novel octapeptide that inhibits in vivo melanogenesis and has great transdermal ability. J Med Chem 2018; 61: 6846-57.

DOI PMID |

| 19. |

Norimoto H, Yomoda S, Fujita N, et al. Effects of keishibukuryoganryokayokuinin (Gui-Zhi-Fu-Ling-Wanliao-Jia-Yiyiren) on the epidermal pigment cells from DBA/2 mice exposed to ultraviolet B (UVB) and/or progesterone. Yakugaku zasshi 2011; 131: 1613-9.

PMID |

| 20. | You YJ, Wu PY, Liu YJ, et al. Sesamol inhibited ultraviolet radiation-induced hyperpigmentation and damage in C57BL/ 6 mouse skin. Antioxidants (Basel) 2019; 8: 207. |

| 21. | Kumar KJS, Vani MG, Wang SY, et al. In vitro and in vivo studies disclosed the depigmenting effects of gallic acid: a novel skin lightening agent for hyperpigmentary skin diseases. Biofactors 2013; 39: 259-70. |

| 22. |

Liu-Smith F, Meyskens FL. Molecular mechanisms of flavonoids in melanin synthesis and the potential for the prevention and treatment of melanoma. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016; 60: 1264-74.

DOI PMID |

| 23. |

Kim YJ. Hyperin and quercetin modulate oxidative stress-induced melanogenesis. Biol Pharm Bull 2012; 35: 2023-7.

PMID |

| 24. |

Ye Y, Chou GX, Wang H, Chu JH, Yu ZL. Flavonoids, apigenin and icariin exert potent melanogenic activities in murine B16 melanoma cells. Phytomedicine 2010; 18: 32-5.

DOI PMID |

| 25. | Enogieru AB, Haylett W, Hiss DC, Bardien S, Ekpo OE. Rutin as a potent antioxidant: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018; 2018: 6241017. |

| 26. | Khan BA, Mahmood T, Menaa F, et al. New perspectives on the efficacy of gallic acid in cosmetics & nanocosmeceuticals. Curr Pharm Design 2018; 24: 5181-7. |

| 27. | Su TR, Lin JJ, Tsai CC, et al. Inhibition of Melanogenesis by gallic acid: possible involvement of the PI3K/Akt, MEK/ERK and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathways in B16F10 cells. Int J Mol Sci 2013; 14: 20443-58. |

| 28. |

Cho YH, Kim JH, Park SM, Lee BC, Pyo HB, Park HD. New cosmetic agents for skin whitening from Angelica dahurica. J Cosmet Sci 2006; 57: 11-21.

PMID |

| 29. | Baek SH, Lee SH. Sesamol decreases melanin biosynthesis in melanocyte cells and zebrafish: possible involvement of MITF via the intracellular cAMP and p38/JNK signalling pathways. Exp Dermatol 2015; 24: 761-6. |

| 30. | Lin KY, Chen CM, Lu CY, Cheng CY, Wu YH. Regulation of miR-21 expression in human melanoma via UV-ray-induced melanin pigmentation. Environ Toxicol 2017; 32: 2064-9. |

| 31. |

Quillen EE, Bauchet M, Bigham AW, et al. OPRM1 and EGFR contribute to skin pigmentation differences between indigenous Americans and Europeans. Hum Genet 2012; 131: 1073-80.

DOI PMID |

| 32. | Robinson N, Ganesan R, Hegedus C, Kovacs K, Kufer TA, Virag L. Programmed necrotic cell death of macrophages: focus on pyro-ptosis, necroptosis, and parthanatos. Redox Biol 2019; 26: 101239. |

| 33. | Zhao MX, Wen JL, Wang L, Wang XP, Chen TS. Intracellular catalase activity instead of glutathione level dominates the resistance of cells to reactive oxygen species. Cell Stress Chaperones 2019; 24: 609-19. |

| 34. | Wang W, Cheng YY, Chen DD, et al. The catalase gene family in cotton: genome-wide characterization and bioinformatics analysis. Cells-basel 2019; 8: 86. |

| 35. | Titz B, Boue S, Phillips B, et al. Effects of cigarette smoke, cessation, and switching to two heat-not-burn tobacco products on lung lipid metabolism in C57BL/6 and Apoe(-/-) mice-an integrative systems toxicology analysis. Toxicol Sci 2016; 149: 441-57. |

| 36. | Hseu YC, Vudhya Gowrisankar Y, Wang LW, et al. The in vitro and in vivo depigmenting activity of pterostilbene through induction of autophagy in melanocytes and inhibition of UVA-irradiated alpha-MSH in keratinocytes via Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathways. Redox Biol 2021; 44: 102007. |

| 37. |

Pillaiyar T, Manickam M, Jung SH. Downregulation of melanogenesis: drug discovery and therapeutic options. Drug Discov Today 2017; 22: 282-98.

DOI PMID |

| 38. | Doolan BJ, Gupta M. Melasma. Aust J Gen Pract 2021; 50: 880-5. |

| 39. | Young Kang H, Ortonne JP. Melasma update. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2009; 100 Suppl 2: 110-3. |

| 40. |

Muallem MM, Rubeiz NG. Physiological and biological skin changes in pregnancy. Clin Dermatol 2006; 24: 80-3.

PMID |

| 41. | Maeda K, Naganuma M, Fukuda M, Matsunaga J, Tomita Y. Effect of pituitary and ovarian hormones on human melanocytes in vitro. Pigment Cell Res 1996; 9: 204-12. |

| 42. | Lee BW, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK. Melasma. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2017; 152: 36-45. |

| 43. |

Liao S, Shang J, Tian X, et al. Up-regulation of melanin synthesis by the antidepressant fluoxetine. Exp Dermatol 2012; 21: 635-7.

DOI PMID |

| 44. | D'Mello SA, Finlay GJ, Baguley BC, Askarian-Amiri ME. Signaling pathways in melanogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17: 1144. |

| 45. |

Pillaiyar T, Manickam M, Jung SH. Recent development of signaling pathways inhibitors of melanogenesis. Cell Signal 2017; 40: 99-115.

DOI PMID |

| 46. | Otreba M, Rok J, Buszman E, Wrzesniok D. Regulation of melanogenesis: the role of cAMP and MITF. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2012; 66: 33-40. |

| 47. | Lyu J, An X, Jiang S, Yang Y, Song G, Gao R. Protoporphyrin IX stimulates melanogenesis, melanocyte dendricity, and melanosome transport through the cGMP/PKG pathway. Front Pharmacol 2020; 11: 569368. |

| 48. | Zhang M, Chen X, Zhang J, Li J, Bai Z. Cloning of a HcCreb gene and analysis of its effects on nacre color and melanin synthesis in Hyriopsis cumingii. PLoS One 2021; 16: e0251452. |

| 49. | Rzepka Z, Buszman E, Beberok A, Wrzesniok D. From tyrosine to melanin: signaling pathways and factors regulating melanogenesis. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2016; 70: 695-708. |

| 50. | Ito S, Wakamatsu K. Chemistry of mixed melanogenesis-pivotal roles of dopaquinone. Photochem Photobiol 2008; 84: 582-92. |

| 51. | Tanaka H, Yamashita Y, Umezawa K, Hirobe T, Ito S, Wakamatsu K. The pro-oxidant activity of pheomelanin is significantly enhanced by UVA irradiation: benzothiazole moieties are more reactive than benzothiazine moieties. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19: 2889. |

| 52. |

Morgan AM, Lo J, Fisher DE. How does pheomelanin synthesis contribute to melanomagenesis? Two distinct mechanisms could explain the carcinogenicity of pheomelanin synthesis. Bioessays 2013; 35: 672-6.

DOI PMID |

| [1] | XU Bojun, TAO Tian, ZHAO Liangbin, ZHENG Hui, ZHAN huakui, GUO Julan. Bushen Tongluo recipe (补肾通络方) improves oxidative stress homeostasis, inhibits transforming growth factor/Notch signaling pathway, and regulates the lncRNA maternally expressed gene 3/miR-145 axis to delay diabetic kidney disease [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2025, 45(3): 561-570. |

| [2] | WU Jiaman, NING Yan, TAN Liya, MA Fei, LIN Yanting, ZHUO Yuanyuan. Difference of the gut microbiota of premature ovarian insufficiency in two traditional Chinese syndromes [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2025, 45(1): 132-139. |

| [3] | MENG Junhua, ZHANG Hong, CAO Yuling, ZHANG Yu, WANG Xiong, SHENG Bi, AN Jing, CHEN Yonggang. Zuyangping (足疡平) formula promotes skin wound healing in diabetic rats [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2024, 44(6): 1194-1203. |

| [4] | ZHENG Peng, MENG Ying, LIU Meijun, YU Di, LIU Huiying, WANG Fuchun, XU Xiaohong. Electroacupuncture inhibits hippocampal oxidative stress and autophagy in sleep-deprived rats through the protein kinase B and mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2024, 44(5): 974-980. |

| [5] | Zubaria Tul Ain, Iram Fatima, Sana Naseer, Sobia Kanwal, Tariq Mahmood. Assessment of phytochemicals, antioxidant, anti-hemolytic, anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer potential of flowers, leaves and stem extracts of Rosa arvensis [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2024, 44(4): 804-812. |

| [6] | WANG Yuezhu, ZHANG Yuyang, QIAO Jiajun, LU Yuyuan, XIA Zhongyuan. Protective effect of thyroid and restores of ovarian function of Buzhong Yiqi granule (补中益气颗粒) on experimental autoimmune thyroiditis in female rats [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2024, 44(2): 315-323. |

| [7] | HUANG Hongmei, YANG Maojun, LI Ting, WANG Dandan, LI Ying, TANG Xiaochi, YUAN Lu, GU Shi, XU Yong. Neferine inhibits the progression of diabetic nephropathy by modulating the miR-17-5p/nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 axis [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2024, 44(1): 44-53. |

| [8] | ZHANG Xiaoying, WANG Ruixuan, WANG Yiqing, XU Fanxing, YAN Tingxu, WU Bo, ZHANG Ming, JIA Ying. Spinosin protects Neuro-2a/APP695 cells from oxidative stress damage by inactivating p38 [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2023, 43(5): 868-875. |

| [9] | LIU Bingbing, LI Jieru, SI Jianchao, CHEN Qi, YANG Shengchang, JI Ensheng. Ginsenoside Rb1 alleviates chronic intermittent hypoxia-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy in db/db mice by regulating the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 signaling pathway [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2023, 43(5): 906-914. |

| [10] | ZHOU Hua, LI Hui, WANG Haihua. Potential protective effects of the water-soluble Chinese propolis on experimental ulcerative colitis [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2023, 43(5): 925-933. |

| [11] | ZHENG Wei, WANG Mingxing, LIU Shanxue, LUAN Chao, ZHANG Yanqiu, XU Duoduo, WANG Jian. Buyang Huanwu Tang (补阳还五汤) protects H2O2-induced RGC-5 cell against oxidative stress and apoptosis via reactive oxygen species-mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2022, 42(6): 885-891. |

| [12] | HENG Xianpei, LI Liang, YANG Liuqin, WANG Zhita. Efficacy of Dangua Fang (丹瓜方) on endothelial cells damaged by oxidative stress [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2022, 42(6): 900-907. |

| [13] | HUANG Qiuyue, YE Hui, SHI Zongming, JIA Xiaofen, LIN Miaomiao, CHU Yingming, YU Jing, ZHANG Xuezhi. Efficacy of Qingre Huashi decoction (清热化湿方) on infection of Helicobacter pylori: inhibiting adhesion, antioxidant, and anti-inflammation [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2022, 42(6): 915-921. |

| [14] | Xing DU, Tianlong LIU, Wendi TAO, Maoxing LI, Xiaolin LI, Lan YAN. Effect of aqueous extract of Astragalus membranaceus on behavioral cognition of rats living at high altitude [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2022, 42(1): 58-64. |

| [15] | CAI Liang, ZONG Daokuan, TONG Guoqing, LI Li. Apoptotic mechanism of premature ovarian failure and rescue effect of Traditional Chinese Medicine: a review [J]. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2021, 41(3): 491-498. |

| Viewed | ||||||

|

Full text |

|

|||||

|

Abstract |

|

|||||